Two-and-a-half years ago when she joined a book club through the Wounded Warriors Project (WWP), a nonprofit organization that provides programs and services for wounded veterans, Torey Reese wasn’t thinking about how much she enjoyed reading or needed some motivation to finish a book. She just wanted to find friends.

Like others in this caregiver’s group, Torey had a husband at home who had been injured during active duty as a Marine. She and her family had relocated to San Antonio, Texas a year and a half earlier. Her second child was born shortly after the move with some health problems that required several surgeries. Because of her family’s healthcare needs at the time, she wasn’t working, and she was feeling pretty isolated. The book club was a way for her to get together with others who shared some of the challenges she was dealing with.

“Pretty much immediately I thought I wanted to be friends with Amanda,” Torey says. “We loved similar types of books, and that just kind of sparked the friendship.”

Amanda Martin was there at the book club because she too cares for a former military husband with serious health issues. Since meeting three years ago, the two have found lots of other things they have in common, including children that are around the same age. And except for their current social distancing because of COVID-19, they and their kids have been inseparable.

But Amanda and her 9-year-old daughter Rita live with primary immunodeficiency disorders, which make them vulnerable to recurrent infections. Amanda depends on intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) infusions twice a month to stay healthy. Rita too receives subcutaneous IG weekly.

“Immune globulin helps control our infections,” Amanda says. “Our lives are so much better because of it. It enables my daughter to go to school. It enables me to be out in the community and to advocate for my husband. I wouldn’t be able to function as well as I do without it.”

When Torey found out about Amanda’s and Rita’s disorder and the life-saving therapy they depend on, she had to help. Immune globulin is not a drug that can be mixed up in a laboratory. It is made from donated human plasma, the golden-colored liquid that remains after the red blood cells are removed. It takes 130 plasma donations to treat one immunodeficiency patient for one year. When donations decrease, so do immune globulin supplies. If there is a shortage, as we had last summer, Amanda and Rita risk having to go a longer period of time between their infusions. They may even have to go without.

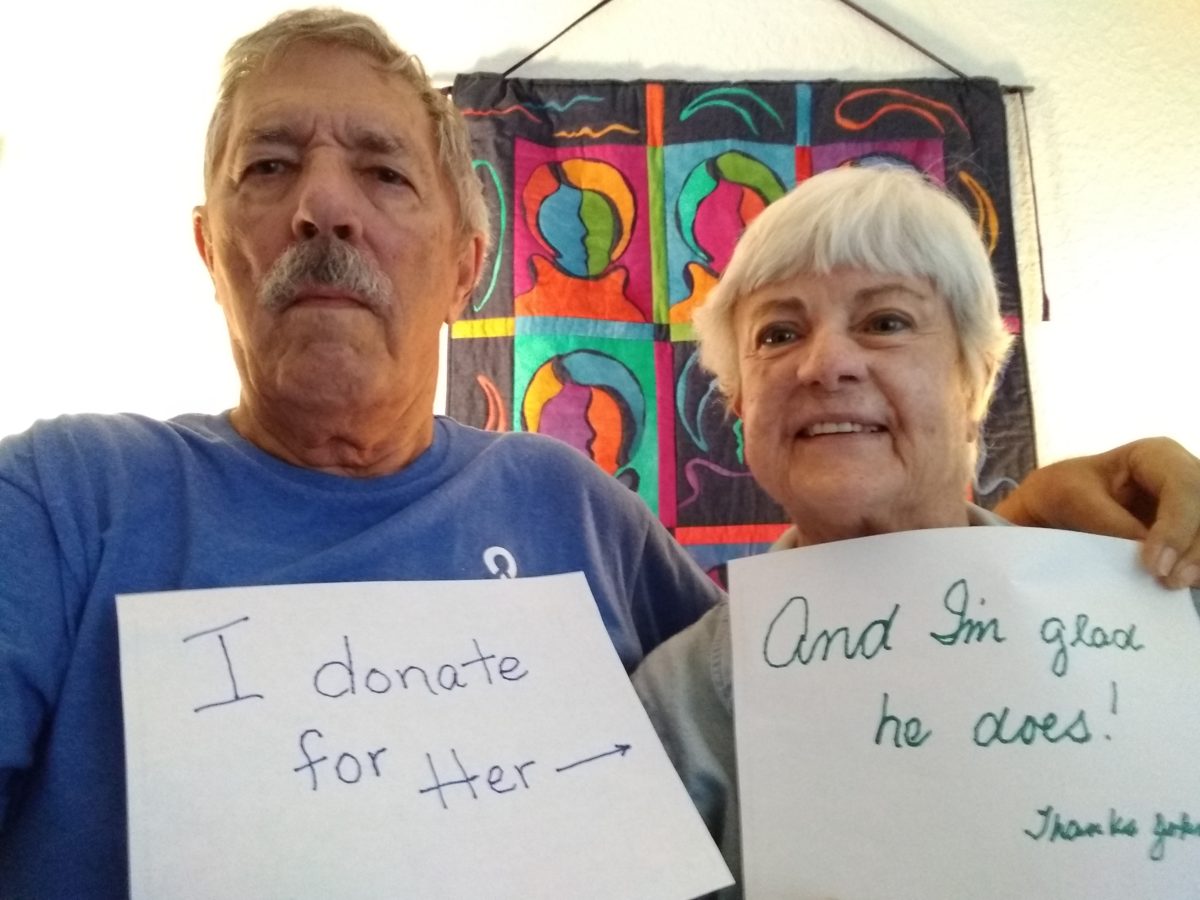

So once a week or so, Torey goes to one of more than 800 certified plasma donation centers in the country to give a bit of her plasma. She wishes she could donate twice a week, which is the maximum donors are allowed. But in addition to caring for her husband and two boys, Cayden 10 and Caspian 3, Torey now works as an accountant for a small nonprofit organization. Once a week is all she can manage right now. Still, this is a long-term commitment for Torey, who has been donating for nearly a year now.

“It’s something I can directly do to help them stay alive and stay healthy,” says Torey, who has donated plasma in the past. “I never knew anybody before who directly benefited from my donations. So when you have a person you care about, who is a real face and a real name and a real story to you, it’s hard to not want to help them. I mean, it’s a minor inconvenience to me, but it’s a major inconvenience to them.”

“I can’t express my gratitude enough for her doing this,” Amanda says with a catch in her throat. “It’s something my daughter and I talk about when we get our infusions. We’re very, very grateful and just lucky that Torey is healthy and willing to do it. This may not seem like a heroic thing to do, but for the people who benefit from it, it absolutely is.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a significant reduction in plasma donations in recent months. CSI Pharmacy, in partnership with the Immune Globulin National Society (IGNS) and their #ItsMyTurn campaign, urge those who are eligible to commit to donating plasma to help avoid a shortage of immune globulin and other life-saving plasma-derived products in the months to come. Reminder: It is important to seek out a certified plasma donation center to be sure your donation is used for IG products. (Donations made at blood banks and the Red Cross are not used to create IG products.)