Many patients with autoimmune disorders and primary immune deficiency diseases depend on regular infusions of immune globulin (IG) to keep them healthy. For most of the nearly four decades since immune globulin therapies have been available, patients have had only one viable option for how this treatment was given. It was only available as an intravenous (IV) infusion.

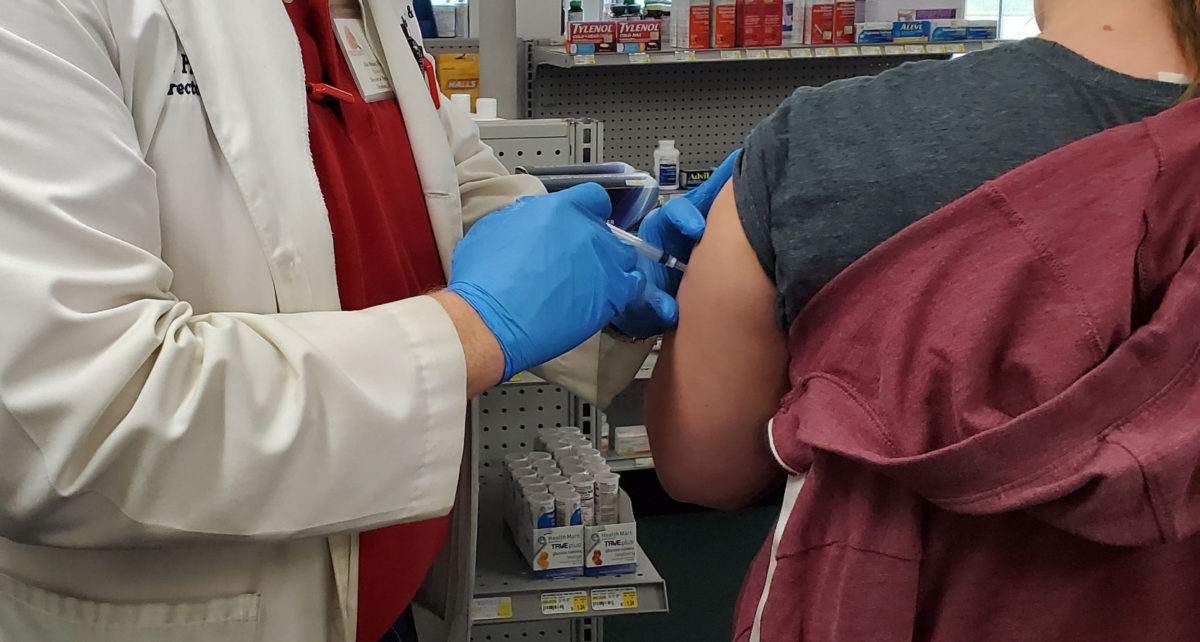

Since 2006, however, when the first IG product was approved for subcutaneous (SC) administration, patients have had a choice about how they received their treatments. Both products are considered equivalent in terms of efficacy, but there are lots of other factors that may make one preferable over the other. Providers usually have their own sense about how IG should be administered, but we asked IG users for their thoughts on the pros and cons of each option.

Convenience is the biggest factor in which route patients prefer. Ironically, both IV and SC users think their choice is most convenient.

Rebecca, for example, has been getting IVIG for 12 years after being diagnosed with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). She speaks for many when she says, “I like that I only sacrifice one day every three weeks for treatment.”

The convenience of once-a-month infusions with IVIG comes at the expense of independence, though. IVIG poses higher risks, because it goes directly into the vein rather than under the skin. So it must be given under a nurse’s supervision, whether that is in the hospital, an infusion center, or at home. This means it also has to take place on a schedule that may not always be convenient.

Those who use SCIG usually take their infusions once a week rather than once every three to four weeks or so. Still they prefer the control they have over when they infuse, because they do it themselves. As Brandina, who has myasthenia gravis, says, “I love that I can administer it myself. The treatment days are flexible, and I can take the medication with me, so I don’t have to plan my vacation around treatments.”

Infusing once a week is also inconvenient for some SCIG users, but for most this is a minor drawback. As Jen, who has specific antibody deficiency, says, “I absolutely love SCIG. There are so many more pros that I could list and only this one con.”

Getting infusions at home, whether it is IV or SC, is also a convenience. This has become especially important since the COVID-19 pandemic has made it less desirable to go to a healthcare clinic. Brynne, whose six-year-old daughter uses IVIG for juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM), was grateful when her overnight hospital infusions were changed to in-home infusions because of coronavirus restrictions.

Making the most of infusion time is something IVIG users have worked into their lives. Sitting in an infusion center or even hanging out at home with a nurse for six to eight hours or more can be a huge inconvenience, but it doesn’t have to be wasted time. Dana, who has dermatomyositis, likes IVIG, because it forces her to take time for herself and relax. And Robin, who has CVID, uses the time to crochet.

Mary, whose husband has myasthenia gravis (MG), prefers to get his IVIG at the hospital infusion center for other self-care reasons. “He loves the heated, vibrating recliner,” she says. “And they provide snacks and lunch.”

Adverse effects can be more of a problem with IVIG. In fact, this is often the reason patients switch to SCIG, which has far fewer reactions. Symptoms can range from fatigue, fever, flushing, chills, and ‘‘flu-like’’ symptoms to more life-threatening reactions like anaphylaxis (severe allergic reaction) and blood clots.

The most frequent side effect is headache, which can last several days and be more severe than a migraine. Some, like Lola, who has Sjögren’s syndrome, even get aseptic meningitis (inflammation of the membrane covering the brain) after infusions. This causes debilitating headaches, dizziness, and other symptoms.

Scar tissue and knots of fluid under the skin from subcutaneous infusions was a drawback for those using SCIG. These knots usually disappear within a few hours, though, and any redness or swelling at the injection site usually decreases over time.

Pain from being stuck with needles is not an insignificant side effect, regardless of whether it’s IV or SC. Whether it’s having to stick oneself multiple times or whether it’s having difficult-to-access veins, nobody likes to feel like a pincushion.

This can be especially challenging for children. Nancy’s nine-year-old daughter has JDM and receives IVIG at a pediatric infusion center. She says having ultrasound to find and insert the IV needle makes a world of difference for her daughter. Being spoiled by the nurses also takes some of the sting out of the whole ordeal.

Fluctuations in therapeutic effect is another reason many people switch to SCIG. An IG dose is mostly metabolized by the body over about 22 days, whether it’s given IV or SC. With IV infusion the dose reaches its peak immediately and dissipates over the next three to four weeks. This means that some patients will feel their symptoms returning as IG levels in the blood go down.

“As I got closer to my next treatment date, I would start to feel the effects of needing my next treatment,” says Karon, who has MG. “After I received it, I could tell I had just received a boost and had more energy.”

Giving IG under the skin makes the blood levels rise more slowly. And because SCIG is given more frequently—usually weekly—IG levels in the bloodstream fluctuate far less, so patients don’t feel that fatigue and other symptoms returning.

Whatever you decide about IG therapy, Lea, who has used IVIG for 22 years to treat CVID, offers this important advice: “You have to listen to your body and watch how it reacts to everything and try things until they work for you.”

For those who would like to learn more about IVIG or SCIG, please contact the CSI Pharmacy advocacy team at [email protected].