“It’s like explaining how chocolate tastes to someone who’s never had chocolate,” Rose Mary Istre says of trying to explain dermatomyositis to her friends and family. “They don’t get it.”

When she was diagnosed more than twenty years ago, even doctors didn’t have a good understanding of this autoimmune muscle disease or how to treat it. Which made Rose Mary feel very much alone and anxious. This is also what made her want to find other people with myositis, people who had tasted this sort of chocolate and knew what it was like.

She contacted The Myositis Association who gave her a list of people in the Houston area who had some form of the disease. In those pre-internet days, Rose Mary sent everyone on the list a survey with a self-addressed, stamped envelope, asking about their interest in getting together for some sort of support group. Shortly after that, 48 of the 50 people on that list showed up at Rose Mary’s house for their first meeting, including one woman who literally crawled in the front door because she was too weak to walk.

“That’s how desperate people were to find someone else who got it,” Rose Mary says. “But the best part was, we realized we weren’t alone. There was somebody else out there struggling with the same issues we had. Even if we thought we just couldn’t cope with it, someone else was out there coping. It gave us hope. So we held hands and became friends and formed a support group, a community.”

When Lekiha Morgan was also diagnosed with dermatomyositis five or six years ago, she too realized she needed to talk to someone. Rose Mary’s group in Houston was almost an hour away from her home in Galveston, but knew she needed to get herself there.

“People around me kept saying you don’t look sick, but my body was catching hell,” she says. “It was great to be around people I could relate to. They also knew more about the disease and taught me things that I could bring home and share with my family and my kids to help them to better understand what I was facing.”

Feeling less alone and having words to express what you’re dealing with are only a few of the ways support groups help those who live with rare diseases like myositis. Simply being able to talk about your feelings and share the frustrations of living with a disease that leaves you unable to pick up your baby or walk up the stairs can be very therapeutic. Even caregivers can benefit from this form of social support, developing improved coping, lower stress levels, less anxiety, and finding hope and purpose in life.

Each support group has their own way of doing things, but they often involve opportunities to both share personal experiences and learn from expert speakers. Rose Mary, for example, has tapped contacts in the medical community, including her own treating physician, infusion nurses, a clinical psychologist, art therapists, a tai chi instructor, and even members of the group who have a special talent they can share.

Among the more popular speakers are medical professionals who are experienced in treating myositis. Members are eager for their answers to questions about everything from treatments and side effects to research and “am I ever going to get better.”

Group members don’t give medical advice, but they are able to talk about what worked for them and to guide people on how to navigate where they are with the disease. Still, this personal experience is often more informed than some physicians who have little experience working with a person with myositis.

“I believe we actually have saved lives at our support group,” Rose Mary says. “We’ve had people who wander into meetings who are going to a medical clinic or seeing a doctor who is not following what we have learned to be a really strong protocol in combating this condition. So our group is a good resource to let people know what’s out there, what’s available in the medical community, and who to contact.”

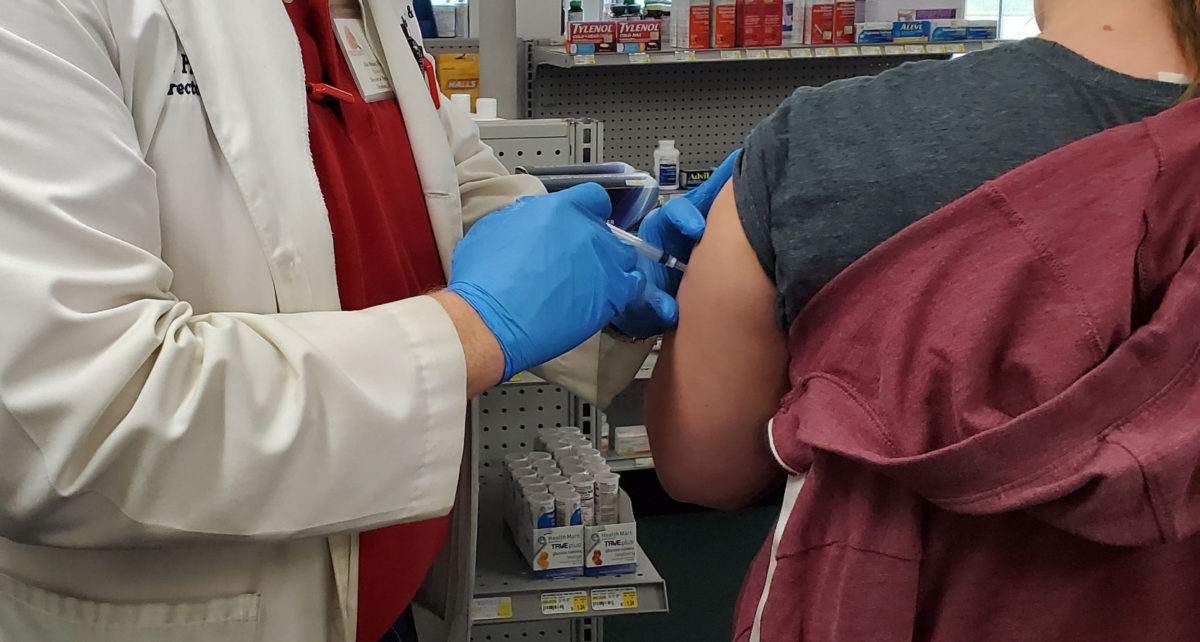

Lekiha is one of those people who was struggling with treatments that were not working well to control her symptoms and were causing complications. At the Houston support group, she learned about intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) therapy, which had been very effective for several people, including Rose Mary.

“I was having a hard time getting around, and I couldn’t work anymore,” Lekiha says. “But the doctor I was seeing at the time said I wasn’t affected to the degree that she felt I needed IVIG. After talking with people at the support group, I ended up going to see a different neurologist who said I was a perfect candidate for IVIG. She said they don’t want you to get to the point where you’re completely immobile and they can’t bring you out of it. Now IVIG is the only medication that I’m on. IVIG changed my life.”

For many people who live with rare diseases like myositis, having a support group to depend on is a life-saving experience.

“I’m so glad and grateful for this group,” Lekiha says. “It’s a scary disease to face by yourself, especially when nobody you know knows anything about it, even doctors. I’m so thankful for these support groups. I don’t think I would be here without them, honestly.”

Rose Mary, too, is grateful for the folks who have shown up at her meetings.

“I don’t know how I would have survived,” she says. “I feel like I needed them more than they needed me. I felt like I finally had purpose in helping somebody else. So many people benefited, and helping them gave me real courage to carry on. I shudder to think where I would be had I not had that support group.”

Resources

CSI Pharmacy provides a resources page with information that may be helpful for all of our patient communities.

The IVIG/SCIG Patient & Provider Support Group is a private Facebook group for those who use immune globulin therapies.

Cure JM Foundation seeks to find a cure and better treatments for Juvenile Myositis (JM) and improve the lives of families affected by JM.

The Myositis Association (TMA) is the leading international organization committed to the global community of people living with myositis, their care partners, family members, and the medical community.

Myositis Support and Understanding (MSU) is a patient-centered, all-volunteer, 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization empowering the myositis community through education, support, awareness, advocacy, access to research, and need-based financial assistance.